The AI Browser Wars

The way we experience the web is about to change radically. So are online business models.

Over the past three decades, the World Wide Web has transformed the digital landscape. Oldsters like me still remember the days when software was stored on 3.5” floppy disks and packaged in white cardboard boxes. It usually came with a hefty user manual, without which the user interface was impenetrable. It was designed to run on one specific operating system, and developers were forced to create multiple versions that ran on PC, Mac and—if they were truly gluttons for punishment—Linux.

Then came the web. Suddenly, software was something that appeared magically in your browser when you loaded a website. Languages like HTML and JavaScript were standardized across platforms, so web apps could be written once and used everywhere. If you needed help, you could turn to online forums like Reddit, Quora or Stack Exchange.

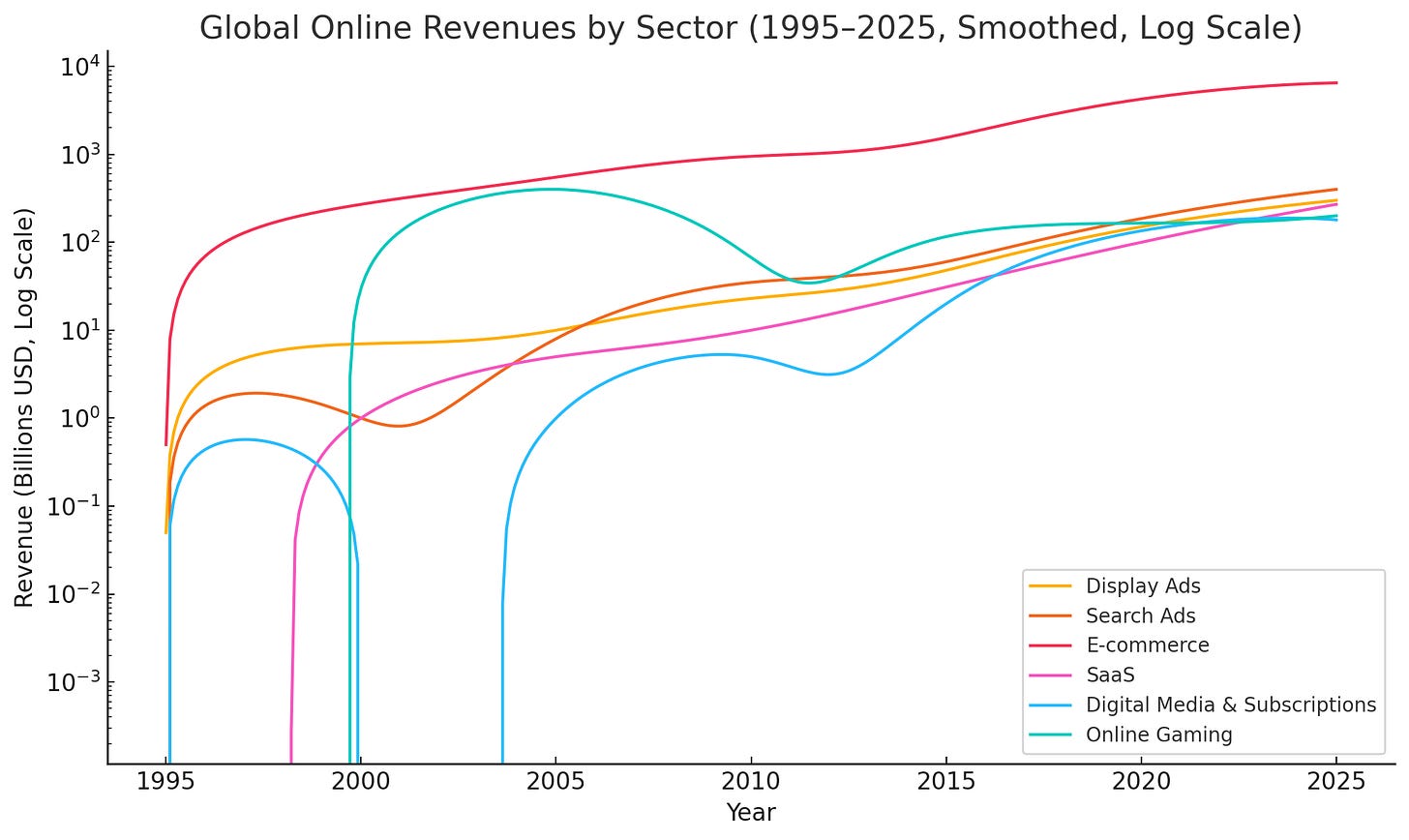

The web also transformed business models. Gone were the days when Bill Gates would complain about “hobbyists” stealing his software. The industry has shifted gradually to a pay-as-you-go model, also known as software as a service. E-commerce revenues have skyrocketed, as an increasing share of consumer purchases has moved online. And—as Google and Facebook have discovered—online advertising offers a seemingly inexhaustible source of high-margin revenue:

We’ve seen two major battles between web browser vendors since the release of Netscape Navigator in 1994. Both were initiated by established companies who saw the web as an existential threat to their existing business models.

The First Browser Wars

During the first browser wars, Microsoft feared that Netscape’s rise would encroach on its Windows revenues. At the time, Windows completely dominated the desktop operating system market with over 80% market share. Microsoft had even figured out a clever way to limit the impact of software piracy: instead of selling directly to end users, it charged PC manufacturers to preinstall Windows on their computers1. By the time Netscape was released, Microsoft was essentially levying a hefty tax on every PC sold.

But what if the web took off? Desktop operating systems might become irrelevant if the only thing that mattered was which browser you use. Maybe Microsoft would be forced face its competition on a level playing field, a scary proposition for a company used to charging monopoly rents.

In May 1995, Gates sent out his famous “Internet Tidal Wave” memo, extolling the importance of the internet2:

The Internet is at the forefront of all of this and developments on the Internet over the next several years will set the course of our industry for a long time to come. Perhaps you have already seen memos from me or others here about the importance of the Internet. I have gone through several stages of increasing my views of its importance. Now I assign the Internet the highest level of importance. In this memo I want to make clear that our focus on the Internet is crucial to every part of our business.

He singled out Netscape as a particularly formidable competitor. So Microsoft grabbed some of the best talent from its deep pool of developers and licensed technology from Spyglass Mosaic—at that point an also-ran in the browser wars. With Gates himself decrying the internet as a potentially existential threat3, the team worked literally day and night to develop the first version of Internet Explorer. Eric Sink of Spyglass described the intense work environment in a blog4 post a few years later:

I was asked to be the primary technical contact for Microsoft and their effort to integrate our browser into Windows 95. I went to Redmond and worked there for a couple of weeks as part of the "Chicago" team. It was fun, but weird. They gave me my own office. At dinner time, everyone went to the cafeteria for food and then went back to work. On my first night, I went back to my hotel at 11:30pm. I was one of the first to leave.

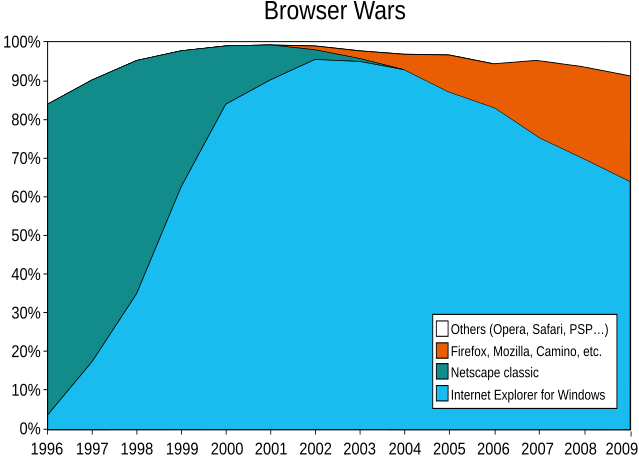

Over the next few years, Microsoft quickly caught up with, then obliterated Netscape:

It achieved this mainly by bundling IE with Windows5, taking advantage of its massive installed base. Over time, it worked in proprietary features that forced websites to decide between supporting other browsers or having access to the latest, greatest IE functionality. Many opted for the latter, and by 2001 IE had achieved absolute dominance.

Microsoft wasn’t making or even trying to make money from Internet Explorer. Its efforts to take over the browser space were aimed only at minimizing the threat Netscape represented to its cash cow Windows business. This strategy was stupendously successful. Netscape was sold to AOL in a face-saving deal that was valued at around $10 billion in stock when it closed in 1999. After a few years of benign neglect, the browser was quietly retired.

The Second Browser Wars

Early versions of IE were basically cobbled together from bubble gum, baling wire and Spyglass Mosaic source code. IE4 was arguably the first truly usable version. IE5 was fairly solid, and Microsoft began to use the “embrace, extend and extinguish” strategy that had cemented its dominance in other areas.

New features like XMLHTTP and ActiveX controls6 were added to the browser. At its peak, IE had 80-90% market share, and it was awfully tempting for web developers to use these features even if they broke compatibility with other browsers. This gave users even more reason to adopt IE, and developers even more reason to support its proprietary features. The ensuing cycle was either virtuous or vicious, depending on your perspective.

IE6’s reign of terror had begun. Many websites declared that they were “best viewed in IE6”. Corporate intranets, which often ran only on some version of Internet Explorer, were forcing some users to stick with the beast well into 2010s.

During this period, Mozilla served as the Rebel Alliance to IE’s Galactic Empire. After essentially giving up on the browser market in 1998, Netscape open-sourced its browser, creating the Mozilla project. The assumption was that only the combined efforts of open-source developers around the world could compete with the IE juggernaut.

At first, the effort faltered. Mozilla made what was, in retrospect, a strategic mistake by trying to market a massive all-in-one suite that encompassed a browser, email client, chat and much more. The product felt bloated, and it struggled to gain adoption.

Eventually, a small group inside Mozilla became frustrated with their lack of success in the market. They set out to create a lean, fast, user-friendly standalone browser that would be more appealing than the unwieldy Mozilla Suite. The result was Firefox. Released in 2004, it stripped away the bloat and introduced appealing new features like tabbed browsing and popup blocking.

By then the market was yearning for an alternative to IE, and Firefox was a smash hit. At its peak in 2009 it achieved 32% market share, forcing Microsoft to start innovating again and take standards support more seriously.

This period also coincided with the rise of Google. Founded in 1998, its search engine was a technical marvel that quickly grew a large user base. After implementing the pay-per-click model for AdWords—its search advertising product—in 2002, it was also throwing off huge wads of cash. Those revenues were closely tied to search engine usage; the more people who used Google for search, the more money the company made.

According to a fascinating contemporaneous account7 by Steven Levy in Wired magazine, Larry Page and Sergey Brin8 had been itching to make their own browser from the earliest days of the company:

"The browser matters," CEO Eric Schmidt says. He should know, because he was CTO of Sun Microsystems during the great browser wars of the 1990s. Google cofounders Larry Page and Sergey Brin know it, too. "When I joined Google in 2001, Larry and Sergey immediately said, 'We should build our own browser,'" Schmidt says. "And I said no."

At the time, Schmidt didn’t feel like they were ready for a head-to-head battle with Microsoft. Instead, Google contributed developers like Darin Fisher to Mozilla’s open source development efforts, where they played a key role. Over time, however, they became frustrated with difficulty of trying to improve a browser while maintaining compatibility with its large existing ecosystem9:

The problem with revamping existing browsers to accommodate this concept is that they have developed an ecology of add-on extensions (toolbars, RSS readers, etc.) that would be hopelessly disrupted by a radical upgrade. "As a Firefox developer, you love to innovate, but you're always worried that it means in the next version all the extensions will be broken," Fisher says. "And indeed, that's what happens."

Microsoft’s decision to build a browser was driven by the perceived threat to Windows revenues that Netscape represented. Similarly, Google was motivated by the possibility that Microsoft might use its dominance in the browser market to control how people use the web. And indeed, that influence—albeit unintentional—was already palpable as Google began to create rich web apps like Gmail and Maps that pushed the capabilities of legacy browsers like IE6 to the limit.

If Firefox was a smash hit, Chrome was a triumph. Many of its key features required amazing feats of engineering, including multiprocess sandboxing and the V8 JavaScript engine, which was an order of magnitude faster than the competition. It also had a sleek minimalistic design aesthetic and an innovative “omnibar” that incorporated search directly into the address bar.

Chrome took on new importance with the release of Bing in 2009. Suddenly there was a credible challenger to the cash geyser that was Google’s search monopoly. Chrome moved to a 6-week release cycle, spinning off new versions much faster than other vendors. Instead of relying on organic growth, they paid for distribution by bundling with popular open-source software like Adobe Flash.

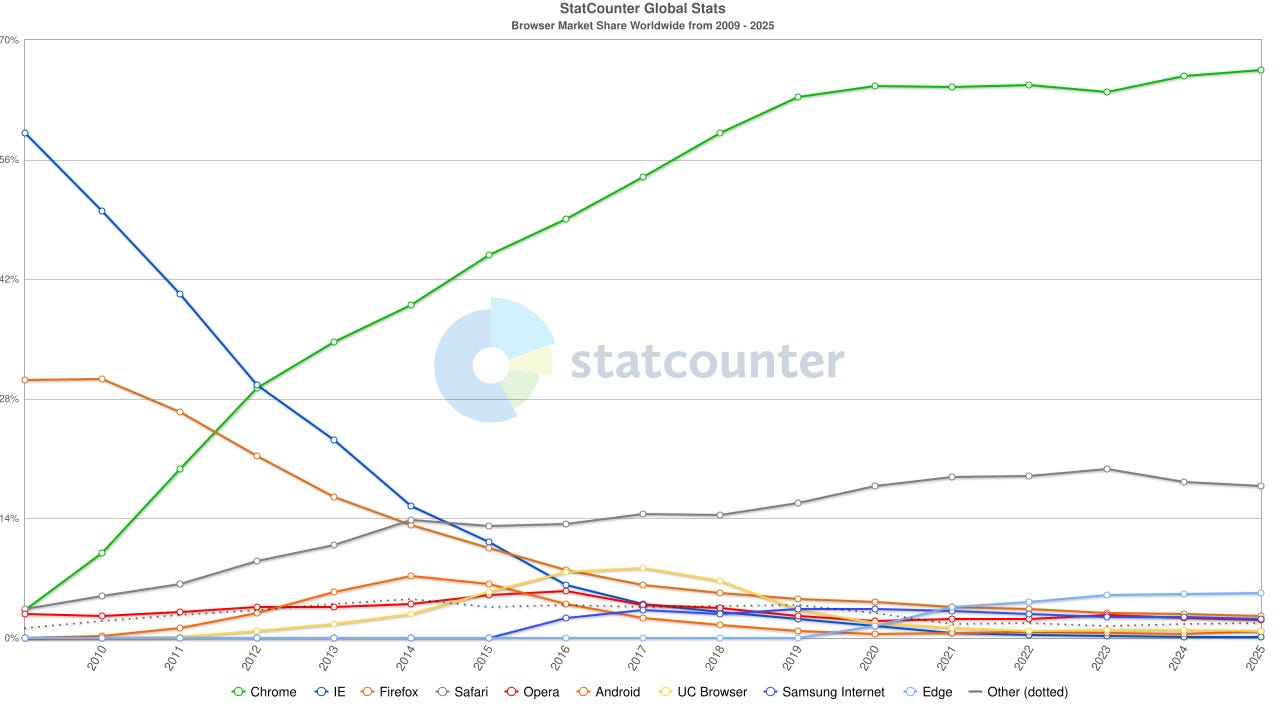

With IE development in the doldrums for the better part of the previous decade, Microsoft was unable to withstand the onslaught of a much faster, more attractive and downright better browser. By 2012, just four years after launch, Chrome had established itself as the world’s #1 browser:

The release of Bing also clarified Chrome’s contribution to Google’s bottom line. It paid for itself not by generating cash, but by saving it. Google was already paying Mozilla about $300 million/year to be the default search in Firefox. They had a similar deal with Apple for Safari, and those payments grew rapidly with the iPhone’s launch in 2007. In 2022, Google paid Apple a reported $20 billion just to be the default search provider on iOS10. For Chrome, with its massive market share, they of course paid nothing.

The AI Browser Wars

Chrome has trounced the competition so comprehensively that the browser wars are now a faint memory. Every other browser is basically niche. The only other even vaguely significant player is Safari, which is preinstalled on the Mac, iPhone and iPad. Moreover, even the nichy alternative browsers almost all use Google as their default search provider.

Yet all of a sudden this Pax Browsana is being shaken up. The reason? AI is upending our assumptions about how we access the web and how companies monetize it.

Before the release of ChatGPT, using then web mostly meant you entered a query into Google, got a bunch of blue links, and clicked one of them. Sometimes the blue link was a search ad, in which case Google made money. Occasionally someone used another search engine, and a different company took a cut. But not very often.

This has been the case for the past 25 years or so. But is this really how people want to use the web, or is it just the best we could do at the time with the technology at hand? After all, in the early days of the web, directories like Yahoo reigned supreme, with search engines just an afterthought11. It took a revolutionary innovation like Google search algorithm to upend the status quo.

Could chat apps offer another such innovation? They have already started to replace the browser for some of the things people do online. The days when ChatGPT would warn you about its limited “knowledge cut-off window” are long gone. Instead of relying on the instantly out-of-date information that was used to train the model, it now goes off and browses the web for you, retrieving the freshest data available12.

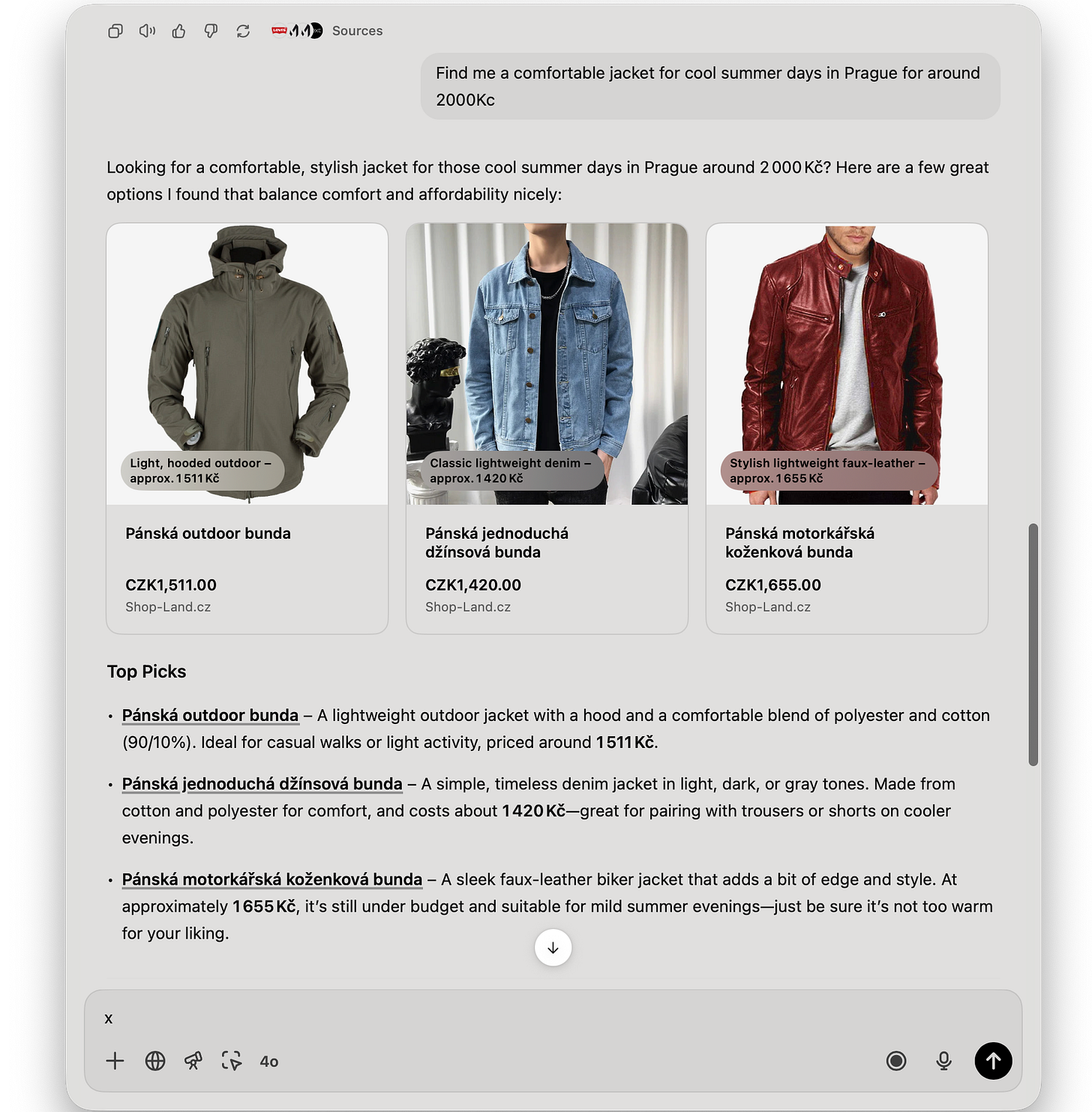

But why stop there? In addition to answering your questions, surely it makes sense for the AI to perform actions for you as well. Sure enough, last month OpenAI announced “ChatGPT agent”, a new feature that does exactly this. The video below shows it searching for a flight from Prague to LAX. Instead of offering full-fledged browsing experience, ChatGPT paints a kind of virtual browser window inside the chat. It’s slow, clunky, and doesn’t feel quite ready for primetime. But the potential is clear.

Other AI vendors are taking different approaches. Anthropic has a “computer use model” that lets the AI take over your computer13 and control any application, including the web browser. More recently, Microsoft added a chat sidebar to its Edge browser and dubbed it “Copilot Mode”, while Perplexity released an entirely new browser with integrated AI capabilities. Opera is preparing something similar, as is OpenAI14.

All of this suggests that AI is enabling the creation of newer, better browsing experiences. The chat interface popularized by OpenAI, Google, Anthropic and others is just a stepping stone. The logical home for these new AI technologies is a wholesale reimagining of the web browser. There are some use cases where it makes sense to view a traditional webpage15. There are probably more, however, where a chat interface—or some combination of the two—makes more sense.

As with previous browser wars, the current shift is motivated to some degree by a desire to adapt the browser UI to accommodate new technologies. Microsoft built IE in part to make the web feel more like the PC desktop. Google needed a fast, flexible platform to run its new generation of dynamic web apps. Now AI vendors want to offer a modern chat interface for tasks where that makes sense, without forcing you to jump back and force between their app and the browser.

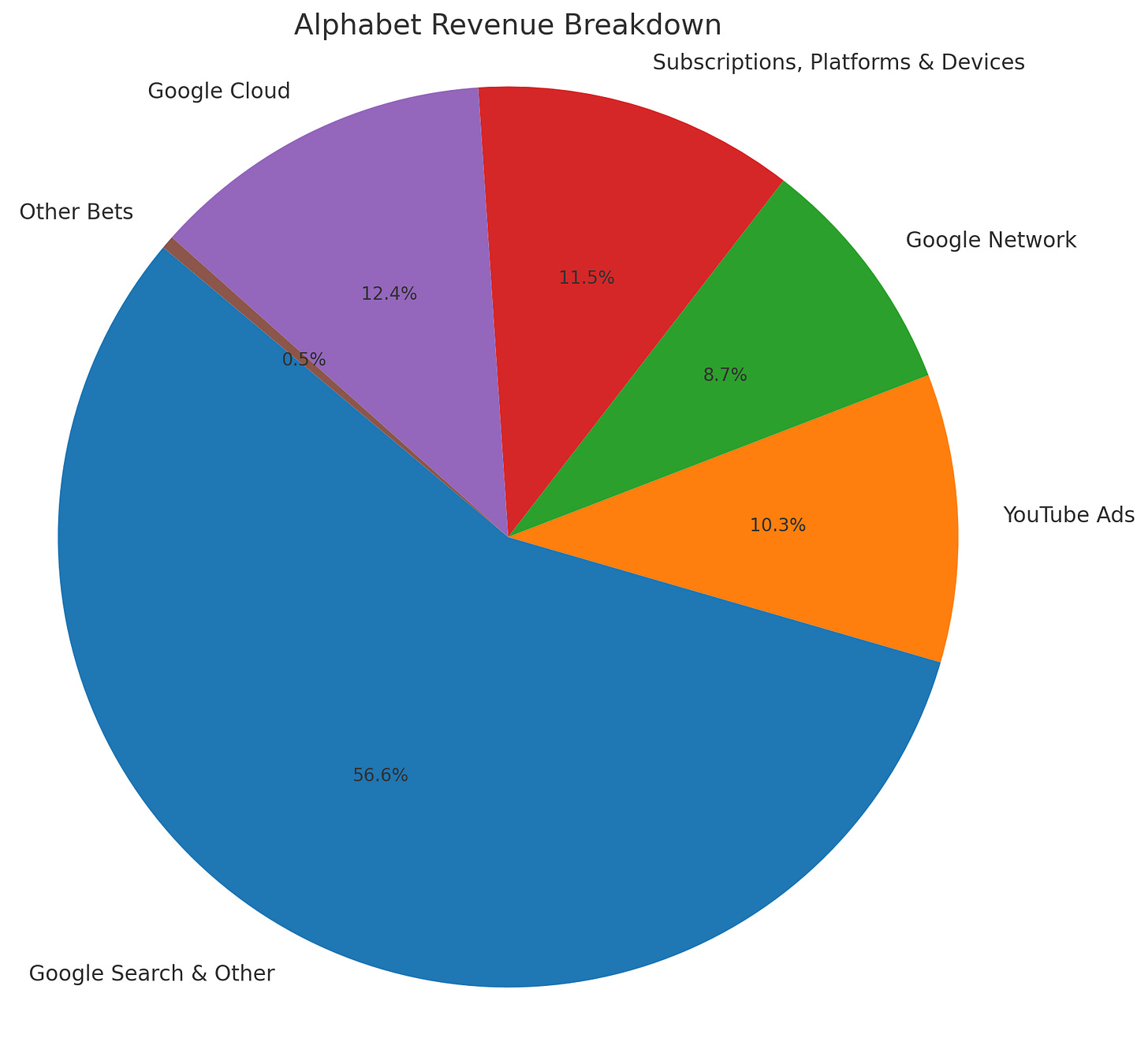

Then there’s the money. Much has been made of the fact that Google’s finances are likely to be heavily impacted as search traffic moves into the chat client. There’s clearly something to this. The majority of revenues for Alphabet—Google’s parent company—come from search. And while the evidence is still anecdotal, there are early indications that AI is already having an effect on user’s search habits:

A new study conducted by Future Publishing with 510 participants from the US and 518 participants from the UK reveals that more than a quarter of Americans (27%) now use AI chatbots like ChatGPT instead of traditional search engines.

Some players are exploring how to generate revenue from inside chat clients. ChatGPT already displays results in a decidedly browser-like way when users ask for product recommendations. They are reportedly experimenting with various schemes for monetizing these results, presumably through affiliate links.

With broad adoption of the Model Context Protocol (MCP)16, which provides a standard interface for chat clients to work with third-party tools, it is easy to imagine users turning to AI to book a holiday rental or flight—with the chat vendor taking a cut of every transaction.

Google is well-placed to fight off its assailants in these new browser wars. It is a both a top contender in the AI space and the undisputed leader in the browser market. At its I/O conference in March, it announced that it was integrating Gemini, its AI technology, into Chrome. The result—rolled out so far to a select group of users in the U.S.—is similar in its approach to Perplexity’s Comet browser.

Google would be well-advised to take the danger seriously, however. As previous browser wars have shown, new technologies open the door to new challengers. After 15 years of unchallenged dominance—and hundreds of billions in high margin search revenues—it will have to start innovating again if it wants to stay ahead.

In fact they made manufacturers pay for every computer they sold, whether it included Windows or not. This helped MS-DOS and then Windows achieve a virtual monopoly on the desktop, since PC vendors had to pay twice if they wanted to preinstall another operating system.

Competitors like Novell cried foul, and the practice was one of the things that got Microsoft into trouble with U.S. Department of Justice in the early 1990s. Microsoft agreed to end the practice in 1994, but as we’ll see, that didn’t end its bundling ways.

The internet was still so new that Gates felt he needed to nudge his lieutenants to give it a try:

Most important is that the Internet has bootstrapped itself as a place to publish content. It has enough users that it is benefiting from the positive feedback loop of the more users it gets, the more content it gets, and the more content it gets, the more users it gets. I encourage everyone on the executive staff and their direct reports to use the Internet.

“One scary possibility being discussed by Internet fans is whether they should get together and create something far less expensive than a PC which is powerful enough for Web browsing,” he wrote in his memo.

Or “weblog”, as folks called it back then.

Once again, this got them into trouble with the DoJ.

XMLHTTP allowed webpages to load data on the fly. It later formed the basis of Ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML), a technology that makes web apps feel more like native desktop apps. ActiveX controls were Windows-proprietary components that offered interactive content and functionality.

Fun fact: Sundar Pichai is prominently featured in the article as a rising star in the Google executive team.

Everyone knows they founded Google, right?

This was the story they told Wired, in any case. I was personally quite involved with the Mozilla community at the time, albeit as an outside contractor. I got the impression that the Google developers were getting frustrated with Mozilla’s bureaucracy and overly cautious attitude.

To some degree, I think this is inevitable within any large open-source effort that doesn’t have a clear authoritative leader. The people who had actually invented Firefox had long since left the organization. There were a lot of brilliant developers still involved, but it wasn’t entirely clear who was running the show. As a result, there was a lot of pushback when the Google folks wanted to make radical changes to the browser.

Eventually they said “fine, I’ll do it myself”, and Chrome was born.

And now it was Google’s turn to attract the ire of the U.S. government..

Once again, I feel compelled to recommend an episode of the excellent Acquired podcast. This one is about the early days of Google, describing the shift from directory to search in fascinating detail.

Because Google doesn’t offer an API for this purpose, ChatGPT and many other chat clients use Bing’s search API.

Nothing frightening about that!

When reading brilliant long-form newsletter posts, for example.

Perfect in so many ways, beautifully written and so joyful to read. Thanks 🙏

Interesting, never knew WWW came with such hefty manual